The History of Poetry

Poetry-making

is much older than writing. Although its origins have been lost to

history and can never be known for certain, the widely-accepted theory

is that poetry arose in early agricultural societies, where it was

spoken or chanted as a spell to promote good harvests. Certainly it was a

part of religious rites and ceremonies in ancient Greece and Rome, and

was the vehicle used for handing down the stories of the people's

struggles and triumphs.

Poetry v Prose

It

is extremely difficult to define poetry and describe the difference

between it and prose, and experts the world over have been

understandably reluctant to do so. On the subject of definitions, the

French poet Paul Valéry (1871-1945) remarked that anybody with a watch could say what time it was, but who could define time itself?

One

attempt at a definition of poetry is that it is written (or recited) in

lines--that instead of running on as prose does, it breaks at certain

points. There is a suggestion of this definition in the original Latin

words for prose and verse: prosus meant 'going straight forth' and versus meant

'returning'. In verse there is a tendency to repetition (to 'return')

and to variation. Of course, if it is the sort of verse that conforms

to an elaborate traditional pattern, it can scarcely be confused with

prose. Even then, though, there are no handy rules for telling whether

it is good poetry or bad poetry, a point often emphasized by the regular

emergence throughout history of poets who were at first scorned, and

later celebrated or vice versa.

Classical Period

Greek Poetry

The earliest known Western poetry consists of two acknowledged Greek masterpieces--the Iliad and the Odyssey. Both of these works are attributed to the legendary Homer, who is supposed to have been a blind wandering minstrel living in Greece in a period put at various times between the eleventh and seventh centuries B.C. The Iliad and the Odyssey are epics--that is, they are long narrative poems about the deeds of heroes. The Iliad tells of the siege of Troy and the Odyssey of Odysseus's (known to the Romans as Ulysses) wanderings after the siege and his journey home.

The earliest known Western poetry consists of two acknowledged Greek masterpieces--the Iliad and the Odyssey. Both of these works are attributed to the legendary Homer, who is supposed to have been a blind wandering minstrel living in Greece in a period put at various times between the eleventh and seventh centuries B.C. The Iliad and the Odyssey are epics--that is, they are long narrative poems about the deeds of heroes. The Iliad tells of the siege of Troy and the Odyssey of Odysseus's (known to the Romans as Ulysses) wanderings after the siege and his journey home.

Cast of Sophocles

Photo courtesy of user.shakko@wikimedia.org.

The

Greeks used poetry not only to celebrate their heroes but to instruct,

to sing of love and to enrich their theatre through plays by such

revered writers as Aeschylus (c. 525-456 B.C.), Sophocles (c. 497-405 B.C.) and Euripides (c. 485-406 B.C.).

Roman Poetry

From its beginning, Latin or Roman poetry was heavily influenced by the Greeks. In the middle of the third century B.C. the Latin poet Livius Andronicus made a translation of the Odyssey--the earliest Latin poetry of any significance surviving today. The first work of real independence however, was the Annals of Ennius (239-169 B.C.), an historical epic of which only fragments survive. Many Roman writers who came after him are still deeply admired. They include Lucretius who in the first century B.C. wrote On the Nature of Things, which has been called the West's greatest philosophical poem--and Virgil (c. 70-19 B.C.) who, among other works, wrote the celebrated national epic, the Aeneid.

From its beginning, Latin or Roman poetry was heavily influenced by the Greeks. In the middle of the third century B.C. the Latin poet Livius Andronicus made a translation of the Odyssey--the earliest Latin poetry of any significance surviving today. The first work of real independence however, was the Annals of Ennius (239-169 B.C.), an historical epic of which only fragments survive. Many Roman writers who came after him are still deeply admired. They include Lucretius who in the first century B.C. wrote On the Nature of Things, which has been called the West's greatest philosophical poem--and Virgil (c. 70-19 B.C.) who, among other works, wrote the celebrated national epic, the Aeneid.

Anonymous Portrait of Chaucer

Photo courtesy of wikimedia.org.

Medieval Period

The

medieval period witnessed the emergence of a variety of poetry written

in the vernacular. The epic masterpieces of the age included the Old

English alliterative poem Beowulf, France's La Chanson de Roland and the Spanish Poema del Cid.

There was also religious poetry, versified romance, and lyric poetry

(literally poetry to be accompanied by a lyre, but also subjective

poetry imbued with melody and feeling).

The great names among medieval poets included Dante Alighieri (1265-1321), Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1340-1400), Saint Francis of Assisi (1181-1226), and the notable Parisian thief and brawler, Francois Villon (c. 1431-63).

The great names among medieval poets included Dante Alighieri (1265-1321), Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1340-1400), Saint Francis of Assisi (1181-1226), and the notable Parisian thief and brawler, Francois Villon (c. 1431-63).

Rennaisance Period

The most celebrated lyric form of the period was the sonnet, which the scholar and poet Petrarch (1304-74) had perfected in Italy. Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503-42) introduced the form to Renaissance England, where Henry Howard, the

Earl of Surrey (1517-47) is said to have fixed the rhyme scheme for the

sonnet's standard fourteen lines: abab, cdcd, efef, gg. William Shakespeare (1564-1616) used the form to write lasting poetry.

Opening page of a 1720 illustrated edition of Paradise Lost by John Milton. Photo courtesy of wikimedia.org.

The Earl of Surrey is also said to have invented blank (unrhymed) verse. The brilliant young poet Christopher Marlowe (1564-93) used this form in his writing for the English theatre, but his early death allowed Shakespeare to fashion blank verse into a medium for his own much-celebrated plays.

Perhaps the greatest Renaissance figure in English poetry was John Milton (1608-74) who, when aged and blind, created his masterpiece, Paradise Lost (published

1667). He was already blind in 1652, when he was acting as Latin

Secretary to Oliver Cromwell's Commonwealth of England, and was assisted

in carrying out his duties by another remarkable poet, Andrew Marvell (1621-78). Marvell belonged to a group of writers whose preoccupations won for them the title of the Metaphysical Poets.

Toward the English Romantics and Victorians

In 1711, Alexander Pope (1688-1744) published his Essay on Criticism

in which he set out in verse his agreement with the theory that poetry

involved imitation, that its subject should be conveyed through the

poem's metre (rhythm) and sound.

Later, with the rise of the Romantic movement, the emphasis in poetry shifted to imagination and expression. William Wordsworth (1770-1850) spoke of the processes behind poetry as 'the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings'.

Tis not enough no harshness gives offence,

The sound must seem an Echo to the sense...

Later, with the rise of the Romantic movement, the emphasis in poetry shifted to imagination and expression. William Wordsworth (1770-1850) spoke of the processes behind poetry as 'the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings'.

Another of the great Romantics was Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822),

a poet of wide range and a passionate critic of privilege. Some of the

ideas circulating after the French Revolution are expressed in his Song to the Men of England.

Wherefore feed, and clothe, and save,

From the cradle to the grave,

Those ungrateful drones who would

Drain your sweat -- nay, drink your blood...

The towering poetic figure for the Victorians was Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809-92), whose poems were known by a great part of the populace. Works such as The Lotus Eaters were much admired.

It has been said that no more accomplished craftsman than Tennyson has ever written English verse. However, it is only recently that his reputation has begun to revive after the eclipse of Victorian taste in the early twentieth century.

It has been said that no more accomplished craftsman than Tennyson has ever written English verse. However, it is only recently that his reputation has begun to revive after the eclipse of Victorian taste in the early twentieth century.

Influences and Modern Poets

In the nineteenth century, influential experiments in metre were made by Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-89) and the American Walt Whitman (1819-92). Hopkins invented a 'sprung rhythm' suggesting natural speech, and in the United States, Whitman produced a free-verse style which was widely emulated.

Poetry now gradually came under the same influences as those that affected painting and music, and which made twentieth-century styles so different from those of all preceding periods.

Poetry now gradually came under the same influences as those that affected painting and music, and which made twentieth-century styles so different from those of all preceding periods.

In France, the poets Paul Verlaine (1844-96), one of the first Symbolists, called for vagueness and music in poetry, and Arthur Rimbaud (1854-91) made an influential demand for 'derangement of all the senses' and for the poet to become a seer.

In the early twentieth century, poetry was affected by the Dada movement, with its attacks on all tradition, and then by the Surrealists.

In the early twentieth century, poetry was affected by the Dada movement, with its attacks on all tradition, and then by the Surrealists.

Photo courtesy of wikimedia.org.

The first Surrealist manifesto (1924) was drawn up by the French poet André Breton:

it urged artists to adopt 'pure psychic automatism', and to explore the

world of dreams and the subconscious, of madness, drugs and

hallucination.

The Surrealists were immensely influential. So in a rather different way was the expatriate American poet, Ezra Pound (1885-1972), who had issued the manifesto of the Imagists (c. 1912-14), calling for direct and sparse language and precise images. Pound promoted the work of an array of splendid talents, among them the great Irish poet, W. B. Yeats (1865-1939), D. H. Lawrence (1885-1930) and Robert Frost (1874-1963). He also assisted in editing one of the great poems of the century, T. S. Eliot's (1888-1965) The Waste Land.

The Surrealists were immensely influential. So in a rather different way was the expatriate American poet, Ezra Pound (1885-1972), who had issued the manifesto of the Imagists (c. 1912-14), calling for direct and sparse language and precise images. Pound promoted the work of an array of splendid talents, among them the great Irish poet, W. B. Yeats (1865-1939), D. H. Lawrence (1885-1930) and Robert Frost (1874-1963). He also assisted in editing one of the great poems of the century, T. S. Eliot's (1888-1965) The Waste Land.

'In the arts an appetite for a new look is now a professional requirement', wrote

the American critic Harold Rosenberg in the early 1960s; and the need

to 'make it new', to avoid the cliche (in attitude or words), to find

fresh ways of expressing contemporary life is still the concern of a

great many poets.

Among the important figures in twentieth-century English-language poetry not already mentioned are the English-born W. H. Auden (1907-73) and Ted Hughes (1930-98); the Welsh Dylan Thomas (1914-53) and the Americans Wallace Stevens (1879-1955) and Allen Ginsberg (1926-97).

Among the important figures in twentieth-century English-language poetry not already mentioned are the English-born W. H. Auden (1907-73) and Ted Hughes (1930-98); the Welsh Dylan Thomas (1914-53) and the Americans Wallace Stevens (1879-1955) and Allen Ginsberg (1926-97).

John Keats' tombstone, Protestant cemetery, Rome, Italy. Photo courtesy of wikimedia.org.

Should a Poet Write His Own Epitaph?

John Keats (1795-1821), like his contemporary Shelley, was a major figure among the English nineteenth-century romantic poets. Despite having created such great poems as Ode on a Grecian Urn and On First Looking Into Chapman's Homer, Keats, condemned to die young of tuberculosis, wrote a dispirited summary of his achievements for his epitaph: "Here lies one whose name was writ in water." But critics and readers throughout history have not agreed with him and it seems likely that the name of John Keats will last as long as English poetry is read.

History of poetry

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For a more in-depth table of the history of poetry, see List of years in poetry.

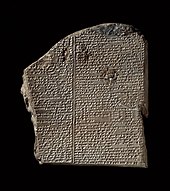

Poetry as an art form predates literacy. Some of the earliest poetry is believed to have been orally recited or sung. Following the development of writing,

poetry has since developed into increasingly structured forms, though

much poetry since the late 20th century has moved away from traditional

forms towards the more vaguely defined free verse and prose poem formats.Poetry was employed as a way of remembering oral history, story (epic poetry), genealogy, and law. Poetry is often closely related to musical traditions, and much of it can be attributed to religious movements. Many of the poems surviving from the ancient world are a form of recorded cultural information about the people of the past, and their poems are prayers or stories about religious subject matter, histories about their politics and wars, and the important organizing myths of their societies

"A poem is an arrangement of words containing meaning and musicality. Most poems take the form of a series of lines separated into groups called stanzas. A poem can be rhyming or nonrhyming, with a regular meter or a free flow of polyrhythms. There is debate over how a poem should be defined, but there is little doubt about its ability to set a mood" .

Identification

-

A poem is identifiable by its literary and musical elements. For example, metaphor and alliteration are common in many poems. Another hallmark of a poem is its brevity, or ability to say much in few words. This requires layered meaning, as in the use of symbolism. A common example of symbolism is the bald eagle, which is a bird, but in the United States also represents the nation as a whole. A poem need not rhyme or contain a consistent meter to qualify as such, but those elements are also common to many poems.

Features

-

A poem can contain any number of features. Usually a poem is broken down into lines and stanzas. They can contain full sentences or just fragments, or a combination. The rules of grammar can be stretched, but this skill is a bit mysterious. Many poets maintain that a poem must demonstrate mastery over one's vernacular even while circumventing it. A poem can be happy or sad, simple or complex, traditional or rebellious.

Function

-

The hallmark of a poem is that it says much in few words. It can exist within a framework of prose, or it can exist on its own. Its chief function is to lend insight, poking its nose into unseen corners, sniffing out signs of life where none were detected before. A poem can evoke awe, inspire action or provide food for thought. It can provide an amusing escape (as in humor), or it can command solemnity (as in religious hymns). A poem can also function as an end unto itself.

Benefits

-

The benefits of a poem often begin where those of prose leave off. A poem can stretch the rules of grammar a bit more, using inventive line breaks or punctuation to accentuate a phrase. Poetry emphasizes the musical use of words for their own sake in addition to providing meaning and context. Brevity is another notable benefit of poetry.

Expert Insight

-

The celebrated American poet Edgar Allan Poe said, "Poetry is the rhythmical creation of beauty in words." He believed that a poem was there to be an aesthetic thing unto itself, not just a vehicle for some other agenda. On the mysterious and ineffable nature of what constitutes a poem, the poet-naturalist Henry David Thoreau said, "My life has been the poem I would have writ / But I could not both live and utter it." In other words, poetry has a life of its own.

-

No comments:

Post a Comment